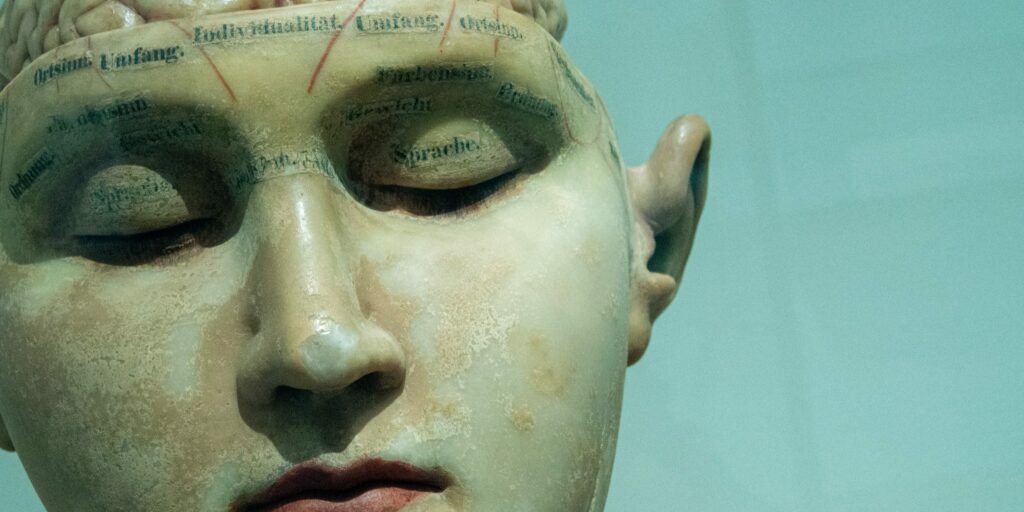

When we learn new skills, whether it’s speaking an unfamiliar language, dribbling a soccer ball, or playing the violin, we experience more than a metaphorical shaping of the mind—the brain physically adapts, too. This capacity to adapt is known as “neuroplasticity,” and it allows the brain to change itself depending on circumstances and optimize the neural pathways we frequently use. Let’s take a look at the fascinating way neuroplasticity shapes the brain so we can better understand the process of learning.

How Neuroplasticity Restructures the Brain

Instead of being a fixed structure, the brain adapts to new information and redirects functions to different regions through this ability called neuroplasticity. What do these changes look like? If we take on the cello, for instance, the area of our brain responsible for finger movement in our fingering hand will enlarge and become more active. With extensive practice, our brain will recruit more neurons for the task, strengthening connections and building complex networks that specialize in playing the instrument.

Studies have shown that the brain area responsible for left-hand movement in violinists and other string instrument musicians, their fingering hand, was larger than in non-string instrument players. At the same time, the results showed that the brain area responsible for right-hand movement in the same string instrument musicians, the bow hand, was similar to that of non-string instrument players.

In other words, the brain area controlling the fingering hand of violinists, cellists, and bassists was overdeveloped, while the one responsible for the bow was average. The results indicate that the string instrument musicians were not born with more complex brain structures for using their hands—had that been the case, they would have shown larger brain areas for both of them and not just one—but instead, that their brain had changed in response to the demands and use of their fingering hand, directing more energy and resources to the area responsible for its movement.

Mental and Physical Skills Elicit Change

Our brain’s capacity to change itself does not apply only to physical skills like playing an instrument but to mental skills as well, like memorizing chess moves or mapping the streets of a city. When scientists examined the brain structure of London cab drivers and compared them to non-cab drivers of the same age group, they found that the cabbies’ posterior hippocampi, responsible for spatial navigation skills, was much larger than in non-cab drivers.

Their study also revealed a direct correlation between the time spent working as a cab driver and the size of the brain area recruited for spatial navigation skills. The longer their career behind the wheel, the bigger the area used for the task. These brain changes occurred over time and didn’t develop without years and years of practicing their craft.

Practice Leads to Specialization

Now that we know the brain has this incredible capacity to change, how can we encourage neuroplasticity as we learn a new skill? The answer lies in a fundamental principle of learning and mastering skills: practice. When we practice, our brain changes to specialize, and the more we practice, the more pronounced the effect.

For example, imagine we are on a hike, and we come across a field of high grass. There’s no path ahead, so we slowly make our way through the grass. The next day, we go on the same hike and face the field again, but this time we can more easily follow the trail of tamped-down grass. Every time we follow the same route, we make it more accessible to walk next time.

Neural pathways work in a similar way. First, we create a primary neural connection for a behavior or thought process, the rough trail going from one neuron or group of neurons to another. But as we keep using the connections, they become faster and stronger, allowing information to move more efficiently from one side to the other. In other words, the more we practice a skill, the more our brains physically change to become better suited for the task.

Neuroplasticity and Mastery

Remember, the more the violinist plays, the stronger the part of their brain that controls finger movements gets. Similarly, the more years a cab driver spends behind the wheel, the more overdeveloped their posterior hippocampi grows.

The same specialization occurs when you practice your craft, whatever it may be. Thanks to neuroplasticity, the brain strengthens connections and forges new paths with every hour you put toward honing your skills. If you give your brain the time it needs to specialize, you can become a master of your craft. For more advice on maximizing your learning capacity, you can find Learn, Improve, Master on Amazon.